Artificial Neural Networks & Deep Learning

How machines learned to perceive, reason, and create — by

mimicking the architecture of the brain

In 2012, a neural network trained on a million images stunned the computer vision world by slashing the best-known error rate nearly in half. That single result set off a revolution that has since reshaped medicine, science, language, art — and the very meaning of intelligence.

What Is an Artificial Neural Network?

An artificial neural network (ANN) is a computational system loosely inspired by the biological neural architecture of the brain. Just as neurons in your brain form complex webs of connections that underlie thought and perception, an ANN is composed of layers of mathematical units — called neurons or nodes — that transform input data step by step until a meaningful output emerges.

The power of this design lies not in any single neuron, which performs only a trivial calculation, but in the collective behavior of millions of them working in concert. Patterns too complex for any hand-crafted rule to capture are absorbed naturally into the network's structure through a process called training.

Core Concept

Each neuron receives one or more numeric inputs, multiplies each by a learned weight, sums the result, and passes it through a non-linear function called an activation function. Billions of these simple operations, stacked in layers, produce intelligence.

The Biological Analogy

Neuroscientist Warren McCulloch and logician Walter Pitts proposed the first mathematical model of a neuron in 1943. The analogy to biology is loose but instructive: biological neurons fire electrical signals when stimulated past a threshold; artificial neurons output higher values when their weighted sum exceeds a threshold. The difference is that biological brains remain far more complex, energy-efficient, and adaptive than anything we have built so far — but the gap is narrowing.

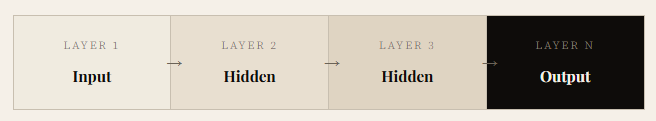

Anatomy of a Neural Network

A neural network is organized into layers. The input layer receives raw data — pixel values, word tokens, sensor readings, or any numerical representation of the world. The output layer produces a prediction, label, or generated value. Between them sit one or more hidden layers, which is where the magic happens.

Within each layer, neurons connect to neurons in the next via weighted edges. During training, these weights are adjusted through an algorithm called backpropagation combined with an optimization method called gradient descent. The network makes a prediction, compares it to the correct answer using a loss function, computes how much each weight contributed to the error, and nudges every weight slightly in the direction that reduces that error. Repeat this millions of times across thousands of examples, and the network gradually learns.

A neural network does not follow rules. It discovers them — sculpting the patterns it needs into the very geometry of its weights.

Deep Learning: Going Deeper

The term deep learning refers to neural networks with many hidden layers — sometimes dozens or hundreds of them. Depth matters because each layer can learn to represent increasingly abstract features of the input. In an image-recognition network, for instance, the first layers might detect edges and gradients, the next might assemble those into textures and shapes, and deeper layers might recognize entire objects or scenes. This hierarchical representation learning is what gives deep networks their remarkable power.

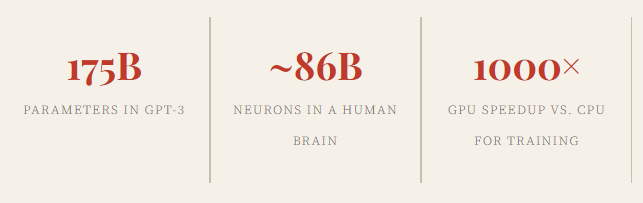

For decades, training deep networks was practically infeasible. Gradients would vanish as they propagated backward through many layers, weights would stop updating, and training would stall. The breakthroughs that unlocked deep learning arrived in the 2000s and 2010s: better activation functions, smarter weight initialization schemes, regularization techniques like dropout, and above all, the availability of vast datasets and massively parallel GPU hardware.

Major Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs are the workhorses of computer vision. Instead of fully connecting every neuron to every other, they use small learnable filters that slide over an input image, detecting local patterns regardless of where in the image they appear. This translational invariance allows CNNs to recognize a cat whether it appears in the top-left corner or the center of a photo. Architectures like ResNet, VGG, and EfficientNet have achieved superhuman accuracy on image classification benchmarks.

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) & LSTMs

For sequential data — speech, text, time series — networks need memory. Recurrent neural networks feed their own output back as input at each time step, giving them a form of short-term memory. Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs), introduced by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber in 1997, added gating mechanisms that allow the network to selectively remember or forget information over long sequences, overcoming the vanishing gradient problem for sequences.

Transformers

The 2017 paper Attention Is All You Need introduced the Transformer, an architecture based entirely on a mechanism called self-attention. Rather than processing tokens one at a time, Transformers process entire sequences simultaneously, computing relevance scores between every pair of elements. This parallelism enabled training on far larger datasets and gave rise to large language models — GPT, BERT, Claude, and their kin — that have redefined natural language understanding and generation.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Proposed by Ian Goodfellow in 2014, GANs pit two networks against each other: a generator that creates synthetic data, and a discriminator that tries to distinguish fakes from real examples. Trained together in this adversarial loop, generators learn to produce remarkably realistic images, audio, and video. Diffusion models have since surpassed GANs in many generative tasks, but the adversarial training principle remains influential.

How Training Works: A Closer Look

| 1943 | McCulloch - | Pitts neuron — the first formal model of an artificial neuron, combining logic and biology. |

| 1958 | The Perceptron - | Frank Rosenblatt's trainable single-layer network showed machines could learn from examples. |

| 1986 | Backpropagation popularized - | Rumelhart, Hinton & Williams demonstrated efficient gradient-based training for multi-layer networks. |

| 1997 | LSTM networks - | Hochreiter & Schmidhuber solved the long-range dependency problem for sequential learning. |

| 2012 | AlexNet - | Geoffrey Hinton's group won ImageNet by a wide margin using a deep CNN on GPUs, launching the modern deep-learning era. |

| 2014 | GANs & Attention - | Goodfellow's generative model and early attention mechanisms opened the door to generative AI. |

| 2017 | Transformers - | the architecture that would power every major LLM arrives from Google Brain, changing NLP forever. |

| 2020s | Foundation models - | GPT-3, Stable Diffusion, Gemini, Claude, and others demonstrate that scale alone can produce emergent, general capabilities. |

How Training Works: A Closer Look

Training a neural network is, at its core, an optimization problem. We have a function — the network — with millions of adjustable parameters (weights and biases). We have a dataset of labeled examples. And we have a loss function that measures how badly the network's predictions deviate from the true labels. Our goal is to find the values of all parameters that minimize this loss.

The algorithm that makes this tractable is stochastic gradient descent (SGD). Rather than computing the gradient of the loss over the entire dataset (expensive), SGD computes it over small random subsets called mini-batches. Modern variants — Adam, RMSProp, AdaGrad — adapt the step size for each parameter individually, greatly speeding up convergence.

Overfitting is the perennial enemy of training. A network with millions of parameters can simply memorize the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns. Combating it requires techniques like dropout (randomly zeroing neurons during training), weight decay (penalizing large weights), data augmentation (artificially expanding the training set), and early stopping (halting training before the network overfits).

The Bias–Variance Trade-off

A model that is too simple underfits the data — high bias, low variance. A model that is too complex overfits — low bias, high variance. Deep learning's empirical success challenged the conventional wisdom here: extremely large models, when trained carefully and with sufficient data, often generalize well despite their massive capacity.

Applications Across Domains

| Domain | Application | Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Computer Vision | Object detection, medical imaging, autonomous driving | CNN, Vision Transformer |

| Natural Language | Translation, summarization, question answering, code generation | Transformer (LLM) |

| Speech | Voice assistants, transcription, speaker recognition | RNN, Conformer, Transformer |

| Science | Protein folding (AlphaFold), drug discovery, climate modelling | Graph NN, Diffusion Models |

| Generative Art | Image synthesis, music generation, video creation | Diffusion Models, GANs |

| Reinforcement Learning | Game playing (AlphaGo), robotics, recommendation systems | Deep Q-Networks, PPO |

Challenges and Open Questions

Interpretability

Modern deep networks are often called black boxes. We can observe what they do but not easily why they do it. In high-stakes domains — medicine, law, autonomous systems — this opacity is not merely philosophically unsatisfying; it is a practical danger. The field of explainable AI (XAI) seeks tools to probe model internals, from saliency maps and attention visualization to mechanistic interpretability research that attempts to reverse-engineer the algorithms learned inside neural networks.

Data Hunger and Sample Efficiency

Deep networks typically require vast amounts of labeled training data. A child learns to recognize a dog from a handful of examples; a deep network may require tens of thousands. Techniques like few-shot learning, self-supervised pre-training, and transfer learning have dramatically improved sample efficiency, but matching human-level learning from sparse data remains an unsolved problem.

Robustness and Adversarial Examples

Neural networks can be fooled by adversarial examples — inputs perturbed in ways imperceptible to humans that cause catastrophic misclassification. A slight change to pixel values, inaudible to human ears in a speech signal, or a carefully designed sticker on a stop sign can completely mislead a state-of-the-art model. Building networks that are genuinely robust to distribution shift and adversarial attack is an active and urgent research direction.

Energy and Compute Costs

Training large models consumes enormous energy, with a corresponding environmental footprint. A single large-scale training run can emit carbon comparable to the lifetime emissions of several cars. As models scale further, efficiency — through architecture improvements, quantization, pruning, and hardware innovation — becomes not just an engineering goal but an ethical imperative.

The Road Ahead

Deep learning has achieved what once seemed impossible: machines that can converse, reason about images, write software, discover scientific hypotheses, and generate art indistinguishable from human work. Yet current systems remain brittle in ways that biological intelligence is not. They lack robust common sense, struggle with genuine causal reasoning, and cannot fluidly transfer knowledge across domains the way people can.

We have built systems of extraordinary capability out of components of extraordinary simplicity. The deeper mystery is why it works so well.

The frontier of research is moving fast. Multimodal models that jointly process text, image, audio, and video are blurring the lines between modalities. World models that build internal representations of physical reality promise to ground AI in embodied understanding. Neurosymbolic approaches seek to combine the pattern-matching strength of neural networks with the precision and transparency of symbolic logic.

Whether artificial general intelligence lies just beyond the next scaling threshold, or requires fundamentally new ideas, remains genuinely unknown. What is certain is that neural networks and deep learning have permanently altered the trajectory of technology, science, and society — and understanding them is no longer optional for anyone who wishes to engage seriously with the world we are building.

Stay tuned to our site for more updates on AI developments, market impacts, and practical advice for businesses navigating this new landscape.